In the light of the operational issues and constraints discussed in section 2, the overall increases in patronage discussed in section 3, the immediate priorities listed at the start of section 4.2 below and the viability of the alternatives discussed in section 4.3, it is proposed that:

As described in more detail in sections 4.4 to 4.10 below, the principal strategies for CityRail services for the next decade, in the face of the operational difficulties outlined in section 2 and forecast patronage growth, are to:

As already recommended and approved:

A new timetable for CityRail services would be able to change the stopping patterns for several services, making them simpler and more repetitive.

The new 2001 timetable will allow realistic dwell times at stations, reflecting station patronage, and will allow extra time at junction interchange stations. Timetabled running times will increase by between two and five minutes during the peaks.

Work is continuing with the relevant staff and unions to identify the ways in which the coordination centre can enhance its role as the coordination point for all the actions that need to be managed during a major service disruption.

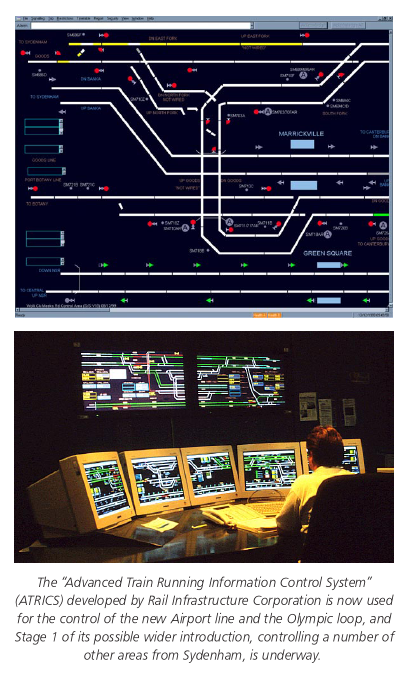

This work is now focussed on the installation of the new control system in the Sydenham signal control complex.

Despite claims made from time to time by the advocates of particular "solutions", there are no "magic bullets" that can provide a complete answer to the difficulties faced by a complex, capacity-constrained and ageing metropolitan rail system such as Sydney's, faced as it is with the prospect of considerable further patronage growth in the short, medium and long terms and the continued need for a mix of longdistance, suburban and "inner city distribution" types of services.

Nonetheless, a number of the "alternatives" merit serious consideration, and elements of them are quite likely to find a place in the more comprehensive and realistic strategies advanced in the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail.

The options for managing rail patronage growth, in addition to the measures outlined in section 4.2 above, include diversions to other transport modes such as private cars and buses, a process actively encouraged in many parts of the world in the second half of the 20th century.

This option is now neither feasible nor desirable, given increasing road congestion, degrading air quality and the severe peak period overloading already experienced by the Sydney bus fleet.

Indeed, the approach now preferred -- not only by rail and public transport agencies but also by road network planners and developers, including the Roads and Traffic Authority -- is to actively manage and reduce the growth in road network demand, by reducing the need for people to rely on private car travel and encouraging the use of more efficient modes of transport, including rail-based public transport.

The Government's target for a halt to the growth of total vehicle kilometres travelled in the greater metropolitan region by 2021, as spelt out in Action for Air and Action for Transport 2010, depends very heavily on boosting rather than cutting rail patronage (see section 3.1).

More specifically, in developing the transport strategies set out in Action for Transport 2010 the Government consciously reinforced this approach by choosing to make major investments in the rail system and bus transitways in preference to major freeway/motorway projects.

As discussed in section 5, the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail proposes a number of longer-term rail development options, for possible implementation after 2021, which would utilise corridors previously reserved for now-abandoned freeways such as the F6, or permit the scaling back or long-term deferral of otherwise essential major road projects.

Another option would be to reduce CityRail service standards, with trains routinely having to carry more passengers than the current maximum of 135% of seated capacity -- equivalent to about 1,200 passengers on suburban trains -- and/or with passengers being forced to stand for longer than the current maximum of 20 minutes.

(The current requirement, barely able to be met on the most congested lines, is that passengers should stand for no more than 20 minutes unless they choose to do so, as many do when they board crowded "fast" services in preference to slower services stopping at more stations.)

This option of carrying more people on each carriage is not practical for double deck rolling stock with only two doors on each side of the carriage. Once the number of passengers reaches about 150% of seated capacity there is a significant reduction in the ability of these trains to maintain schedules and maintain high service frequencies, as it takes a long time for passengers to move out of and into the trains, especially at busy locations like the major city underground stations.

In many overseas cities higher train loads are achieved in inner city areas by using single-deck "metro" style trains with very limited seating, large numbers of standing passengers and up to six doors on each side of the carriage.

If such an approach were adopted in Sydney very large and expensive interchanges between the existing suburban and intercity trains and the new metro trains would need to be constructed, and passengers would experience significant inconvenience, especially in the case of the large numbers of commuters passing through the CBD on their way to other major destinations such as Parramatta and Chatswood.

For these reasons, major European cities faced with similar problems -- even those with established metro systems -- are now choosing to extend their suburban railways in new tunnels through the CBD, rather than continuing to rely on interchanges to metros.

A variant on the metro approach would be to introduce metro services, each carrying up to 2,000 passengers, right out into the suburbs. This would force large numbers of passengers to regularly stand for 40 minutes or more, because even with more than 30 trains per hour the seated capacity would be less than half that of the current suburban services. Nonetheless, such services might ultimately become necessary in the long term, if available line capacity for trains carrying fewer people becomes completely exhausted.

Another variant, which may well be more attractive in the medium to long term, would be to use fast and powerful single deck "metro" style trains, with more seats than traditional metros, on entirely new suburban lines, with totally new and separate operational "sectors", passing through the inner city or Parramatta (see section 5).

In combination with the reduced train separations made possible by the new types of signalling systems likely to be adopted for such lines, this might offer the benefits of relatively high service frequencies and high passenger loads on trains able to use much smaller tunnels and climb steeper gradients, thereby significantly reducing the costs of constructing the new lines and permitting their routes to be more closely tailored to land use requirements and opportunities.

No such dedicated "suburban metro" lines are needed or contemplated for at least the next 20 years, however, as most of the inner areas they would serve have good bus services and are therefore not the highest priority for new rail services. In the longer term, however, continued increases in the density of these areas and consequential local and crossregional patronage demand and road congestion can be expected to shift the balance in favour of the greater capacities and faster travel able to be provided by rail.

Another method of increasing train loads would be to increase the length of the existing style of suburban trains, with a corresponding lengthening of station platforms. This idea is superficially attractive, but there would be massive costs in the platform extensions and associated station reconfigurations, especially on underground lines, and complicated trackwork at the ends of stations would preclude the option in several instances. The option might, however, be an attractive way of increasing capacity on any new railway lines built as entirely separate operational "sectors" in the longer term, such as those discussed in section 5 of this report.

Communications-based signalling systems with in-cab signals, originally developed mainly for high-speed trains, are now under serious investigation and development for metropolitan rail systems overseas.

It seems likely that international standards to ensure the "interoperability" of equipment from different suppliers will become reasonably firmly established in the next few years, thereby reducing the costs of implementing such a system on part or all of the Sydney metropolitan network and helping to ensure the compatibility of any such system with any similar systems introduced elsewhere in Australia.

Communications-based signalling systems are usually classified in terms of three "levels" of functionality, all of which provide Automatic Train Protection (ATP) to prevent trains from overspeeding or passing signals set at "danger". This ATP function could replace the old and very maintenanceintensive technology of mechanical "train stops", which stop CityRail (and soon Countrylink) trains only after they have passed red signals and which do not provide any protection for other long-distance passenger services or freight trains.

With the highest ("moving block") level 3 of functionality, expensive and maintenance-intensive conventional trackside signals and track circuits can be removed and the headways between trains can often be significantly reduced, thereby increasing the capacity of each track. Similar but lesser capacity increases can be achieved with some "level 2" systems, which retain conventional track circuits.

The theoretical capacity benefits of the higher "levels" of communications-based signalling are unlikely to be fully realised in Sydney, however, because of the complex mixes of fast and slow services, the complexity of merging and crossing services with minimal time to spare at numerous flat junctions and the extended dwell times at the busiest stations (up to 90 seconds at Town Hall).

Nonetheless, the gains in line capacity may still be a cost-effective way of handling patronage growth on at least some existing lines, at least in the short to medium term, and there could be clear and more substantial capacity benefits for any future (longer term) new suburban lines forming totally separate operational sectors (see section 5).

The other benefits of such systems, including Automatic Train Protection and enhanced abilities to recover from disruptive incidents, are also attractive, although the signalling control capabilities typically introduced in conjunction with such a system, such as automatic train "route" setting and defect logging, will already be provided by the new computerised signalling control system introduced for the Olympic loop and the Airport line and now being installed at the Sydenham control centre as the first stage of a possible wider rollout in the greater metropolitan region (see section 4.9).

It is therefore proposed that the merits, costs, design and programming of an introduction of communicationsbased signalling will be seriously investigated over the next few years, while other works which will be required regardless of the signalling system are carried out and additional trains able to utilise any newly created capacity are acquired. All new trains will also incorporate provisions for the later easy installation of in-cab signalling.

It is stressed that the proposals for amplifications and other upgradings of the rail network and stations set out in sections 4.4 to 4.10 below are entirely consistent with a communications-based signalling system and will still be required if such a system were introduced.

In other words, communications-based signalling is a possible complement to, and not a substitute for, the works recommended in this report.

Further, any rail system capacity increases flowing from a communications-based signalling system will not significantly affect the timing of the projects identified as essential in the next 10-15 years, including the new inner city route which is likely to be required by between 2011 and 2015 (see sections 4.4 and 4.5). It is only in the longer term that project-deferral benefits might become significant and a factor to be weighed against the potentially substantial costs and risks of introducing the new signalling system.

Within the next year Rail Infrastructure Corporation is planning to commence a detailed investigation of the options for communications-based signalling in the greater metropolitan region, in partnership with private sector experts selected on the basis of a call for expressions of interest.

This will be followed by the installation of a pilot "level 1" or "level 2" system on a selected part of the network, to "prove up" the viability, benefits and robustness of the system prior to its possible wider introduction.

It is highly likely that in the longer timeframes considered in section 5 of this report, if not earlier, some internationally and nationally standardised form of communications-based in-cab signalling will be introduced in the greater metropolitan region.

By international standards CityRail's fares are low, but they are comparable with those in other Australian cities and are controlled by the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal, so substantial changes in fares in order to manage demand are very unlikely.

Further, estimates of price elasticities during peak periods suggest that only a substantial increase in fares would have a noticeable impact on patronage levels, even if this were desired.

In theory rail patronage growth could be reduced by changing the patterns of residential and employment growth in a way that would consciously reduce the role of rail in urban transport.

Any such move would undermine the Government's urban consolidation, air quality and transport objectives.

As discussed in section 3.1, it is unlikely that there will be a reversal of the land-use trends favouring continued rail patronage growth on the main corridors to large employment centres, even though the ongoing spread of urban areas and dispersal of employment locations -- slowed but not halted by urban consolidation -- may continue to reduce rail's overall transport mode share.

The cost estimates reported below are indicative costings only, in 2000/2001 A$ with no escalation. Unless otherwise indicated, they are regarded as being accurate only to within -10% to +30% (in other words, the cost of each project could be up to 30% higher than the figure shown, even if the scope of works is unchanged). Accordingly, at this stage all the cost estimates should be treated with caution.

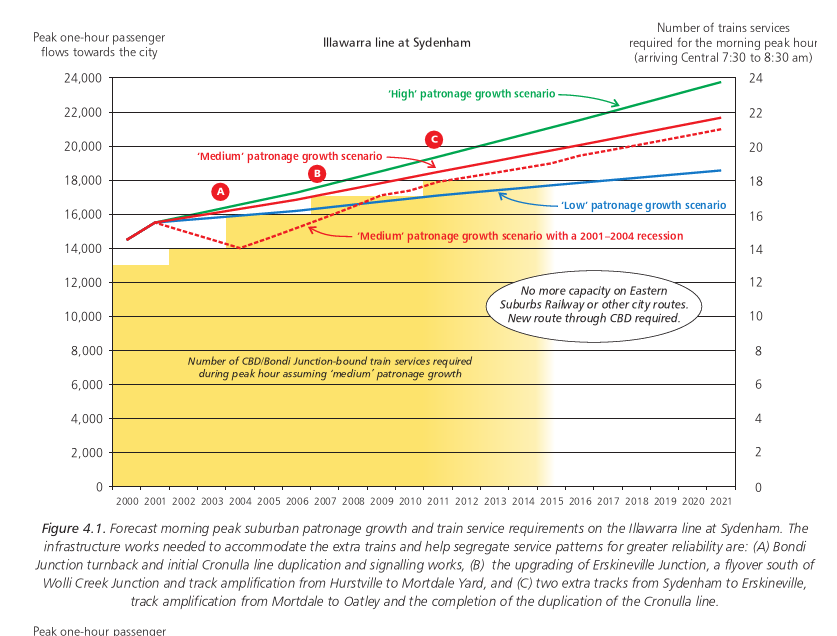

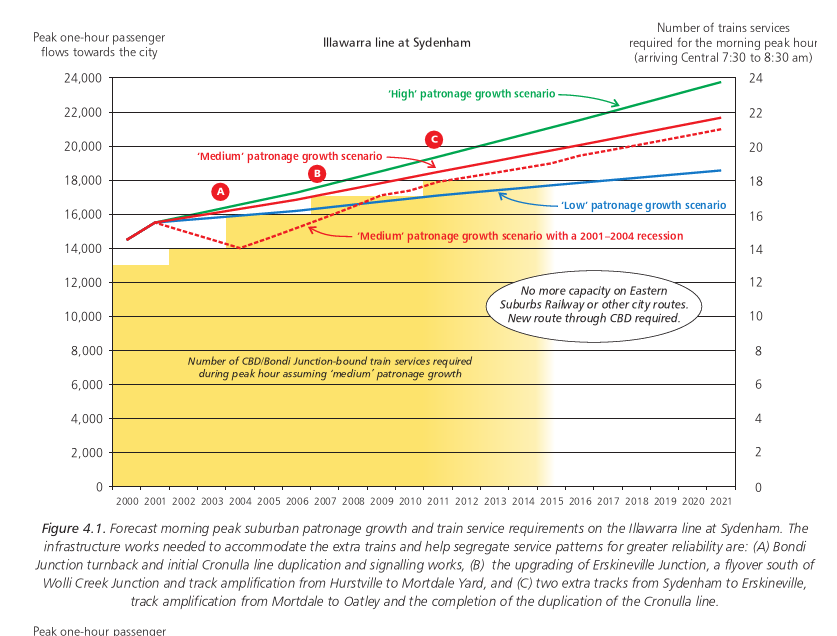

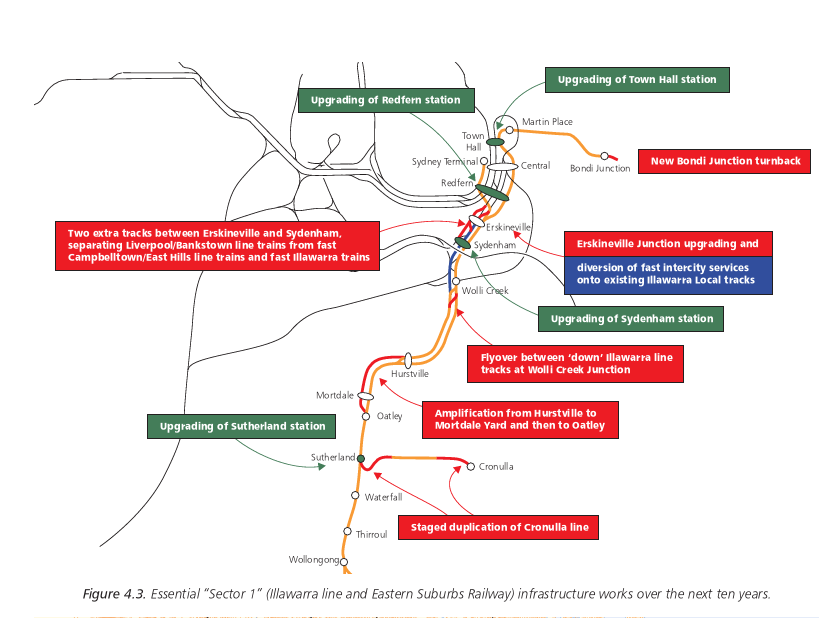

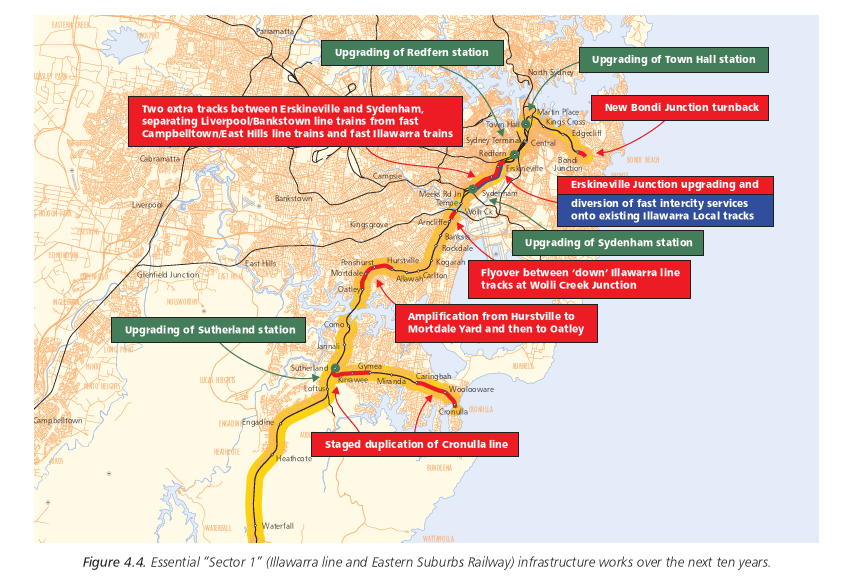

Figure 4.1 shows forecast morning peak suburban (i.e. nonintercity) patronage growth on the Illawarra line at Sydenham under the four growth scenarios discussed in section 3.1, the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario, and the timing of the infrastructure works identified as essential to permit these increases in train services.

In Figure 4.1 (and the equivalent graphs for other corridors discussed below) the left-hand scale and the coloured lines show the number of passengers entering the "CBD cordon" location (in this case Sydenham) on CityRail services arriving at Central between 7:30 and 8:30 am, while the right-hand scale and the yellow bars indicate the number of trains currently arriving between these times and the numbers likely to be required in the future under the "medium growth" scenario.

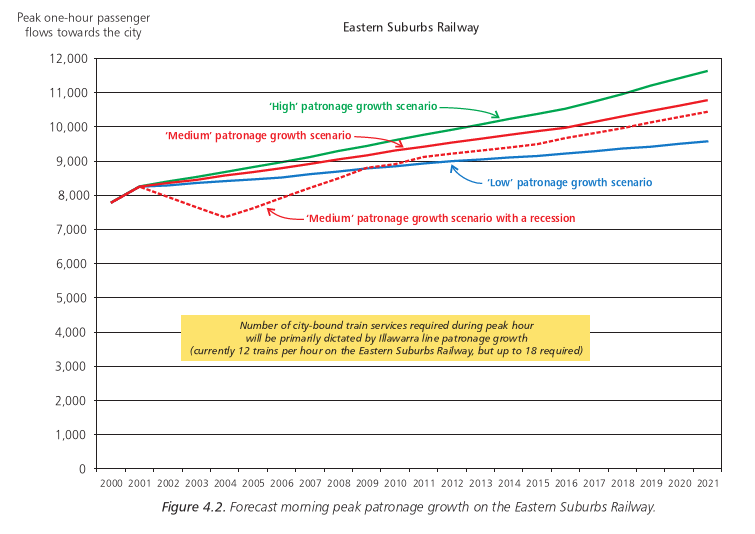

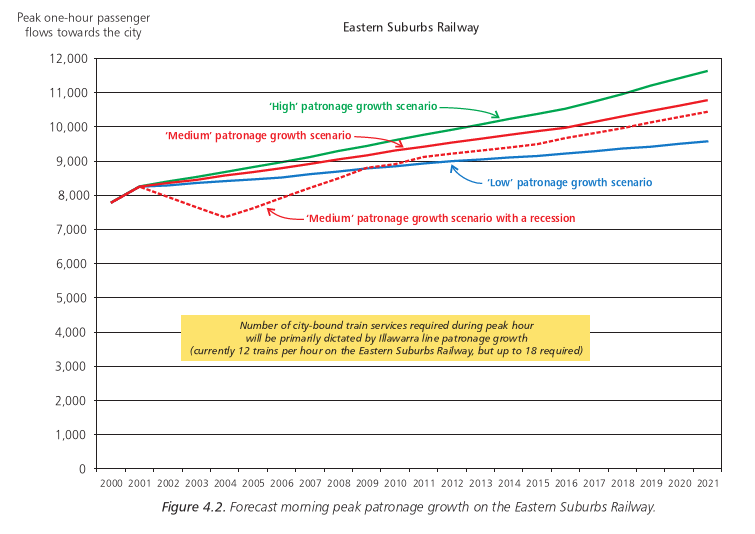

Figure 4.2 shows forecast morning peak CBD-bound patronage growth under the four growth scenarios on the Eastern Suburbs Railway.

The Illawarra line has two tracks from the southern terminus of suburban services at Waterfall to Hurstville and four tracks from Hurstville to the city (two "Illawarra main" tracks and two "Illawarra local" tracks, with no crossovers between these tracks north of Sydenham). The Cronulla branch line is a single track, with a long passing loop between Gymea and Caringbah. The Eastern Suburbs Railway, from Erskineville Junction to Bondi Junction, has two tracks.

At present there are 13 suburban trains to the city on the Illawarra line during the peak hour, 12 of which travel onto the Eastern Suburbs Railway (together with two services from the South Coast) and one of which travels onto the City Circle. (The maximum number of trains able to be accommodated on the Eastern Suburbs Railway, because of "turnback" constraints at Bondi Junction, discussed below, is 14 per hour.)

An extra suburban train is already required on the Illawarra line to relieve overcrowding, and the number of trains required is expected to grow to 17 per hour by 2007 and 18 by 2011.

By this stage, even with the infrastructure works and operational

changes shown in Figure 4.3 and 4.4 and listed below, there will be

no more spare capacity on the Eastern Suburbs Railway for trains from

the Illawarra line and an alternative route through the CBD will be

essential if further growth is to be accommodated. (As will become

apparent below, the same limitation will also apply, within a broadly

similar timeframe, for all other routes into the CBD.)

The essential infrastructure works on this corridor in the next ten years to accommodate the forecast growth are:

This line is experiencing rapid patronage growth and is currently very sensitive to any service disruptions, with the impact of these disruptions often spreading to the entire Illawarra/Eastern Suburbs Railway corridor.

This will need to be followed by an extension of the extra track or tracks to Oatley by around 2011, so that additional fast trains from the South Coast and Cronulla can overtake "all stops" services from Sutherland.

If quadruplication is preferred or required (it would provide much simpler and more robust operational patterns), options such as tunnelling between Penshurst and Mortdale will need to be investigated, to minimise impacts on suburban centres and simplify access to and from the Mortdale Yard. Indicative total cost for Hurstville-Oatley triplication: $100 million.

In addition to these works, several bus-rail interchanges and rail

commuter car parks will need to be upgraded to cater for the

increased demand, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and

life safety works will be required on the Eastern Suburbs Railway, as

discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity

of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

In addition to these works, several bus-rail interchanges and rail

commuter car parks will need to be upgraded to cater for the

increased demand, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and

life safety works will be required on the Eastern Suburbs Railway, as

discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity

of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

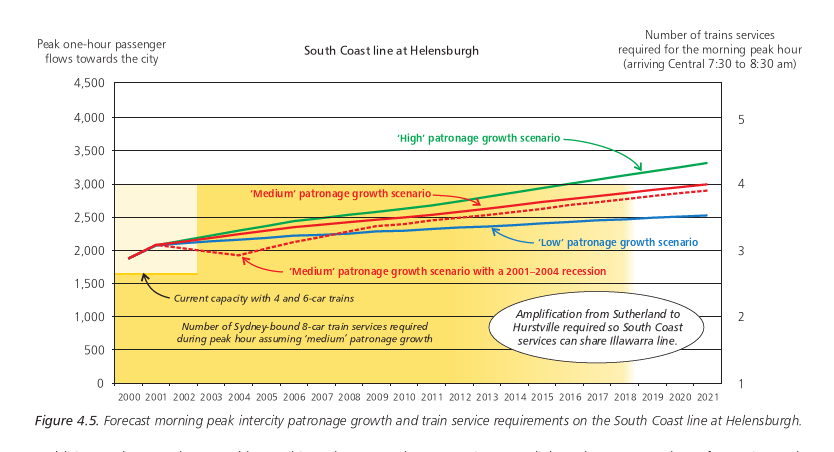

Figure 4.5 shows forecast patronage growth on the South Coast line at Helensburgh under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1 and the capacity of existing intercity train services with the current four and six carriage trains and with the same number of eight carriage trains.

An immediate increase in rolling stock is required to service this route by providing longer trains. This increase has already been approved.

Provided all peak trains are boosted to eight carriages, no additional rail infrastructure is expected to be required on the South Coast line to meet the forecast growth in demand in the next ten years, although latent demand is difficult to estimate. As already indicated, amplifications will be required further north, between Oatley and Hurstville, so the intercity trains can pass the increasing number of local suburban services.

To achieve the benefits of the proposed new high-speed passenger line from south of Waterfall to north of Thirroul, it will be necessary to complete a number of other projects to remove capacity constraints on the South Coast-Illawarra corridor north of this project and in the CBD.

Land slips and other geotechnical problems have long caused difficulties on the South Coast line, necessitating expensive remedial works on a number of occasions. The Stanwell Park viaduct, which is already subject to speed restrictions for these reasons, may need to be replaced during the next ten years, but the timing of the these works is difficult to predict.

As discussed in section 4.6, the Wollongong bus-rail interchange is planned for upgrading by 2003 and the Dapto bus- rail interchange and rail commuter car park are planned for upgrading to cater for rapidly increasing demand in this area by 2005.

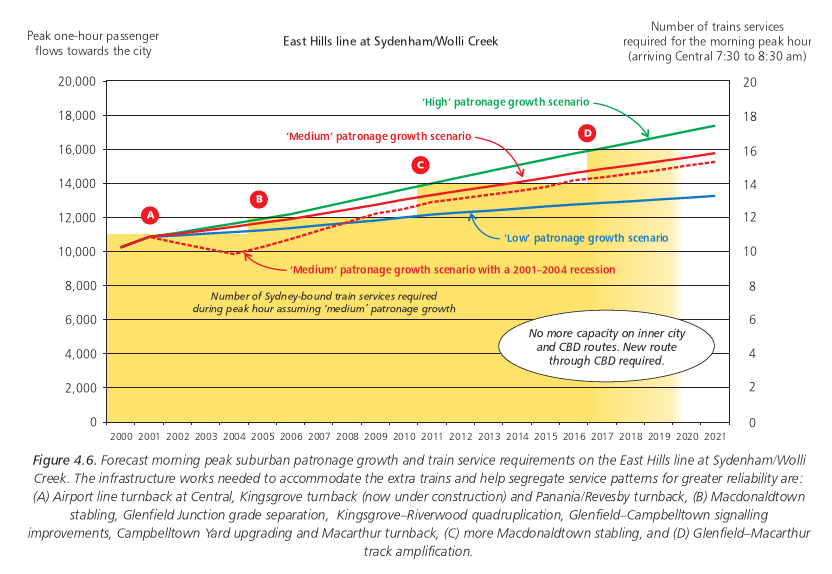

As discussed in earlier submissions by the Office of the Coordinator General of Rail, the East Hills line corridor from Sydenham/Wolli Creek to Campbelltown/Macarthur has the worst CityRail on-time running and service reliability record of the suburban network, and its poor performance adversely affects the entire system.

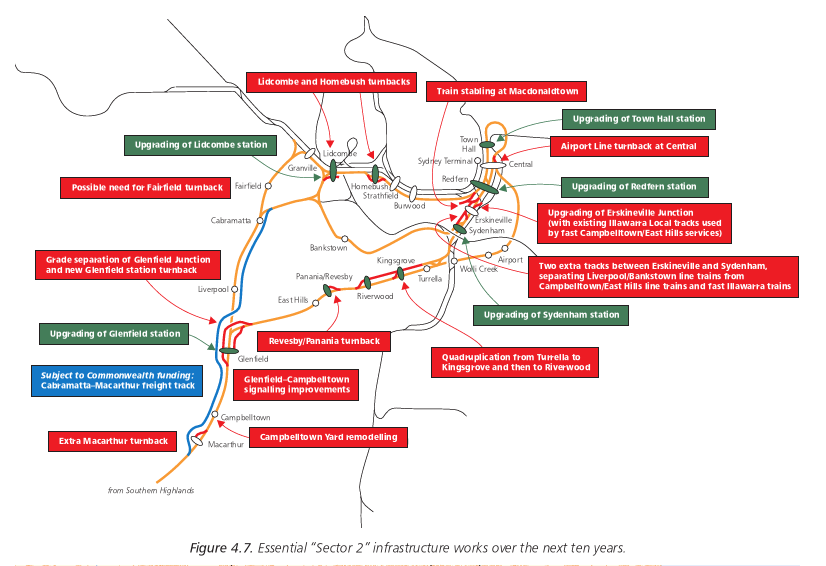

Figure 4.6 shows forecast suburban patronage growth on the East Hills line at Sydenham/Wolli Creek under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1, the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario, and the timing of the infrastructure works identified as essential to permit these increases in train services, which are shown in Figures 4.7 and 4.8.

By around 2011, 14 trains per hour will be required and there will be

no more spare capacity on the City Circle, so an alternative route

through the CBD will be essential if further growth is to be

accommodated.

The essential infrastructure works on the Campbelltown- East Hills corridor in the next ten years to accommodate the forecast growth are:

(Subject to the availability of Commonwealth funding, the construction of a single extra track from Macarthur to Cabramatta, primarily for use by freight services, is a much more urgent priority, preferably commencing in 2002. The estimated cost of this project is about $146 million.)

In addition to these works, several bus-rail interchanges and rail commuter car parks will need to be upgraded to cater for the increased demand, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and life safety works will be required on the City Circle, as discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

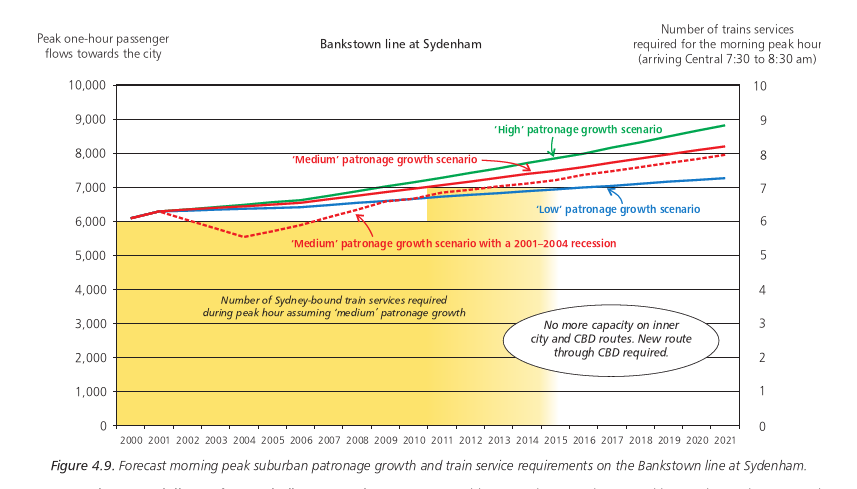

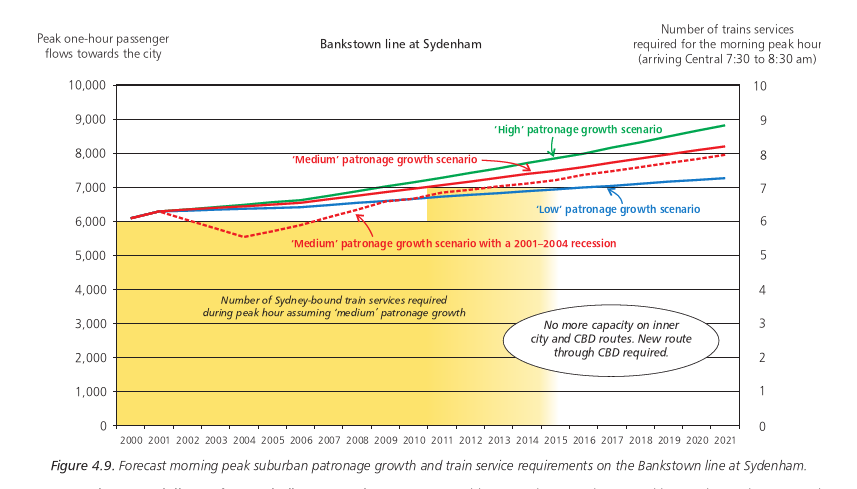

Figure 4.9 shows forecast patronage growth on the Bankstown line at Sydenham under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1 and the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario.

There are currently six peak trains per hour on this twin track line, operating via the City Circle, which could accommodate up to three more trains, two of which could be new "fast" services from Liverpool to the city (the alternative of extra Liverpool services via the Main West line will not be possible, because of increasing congestion on that line).

Once the total number of Campbelltown/East Hills and Bankstown trains exceeds 24 per hour in the peak an alternative route through the CBD will be essential, as the available City Circle capacity will be exhausted.

The essential infrastructure works on the Bankstown line corridor in the next ten years to accommodate the forecast growth are (Figures 4.7 and 4.8):

Again, in addition to these works, the Bankstown bus-rail interchange and rail commuter car park will need to be upgraded, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and life safety works will be required on the City Circle, as discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

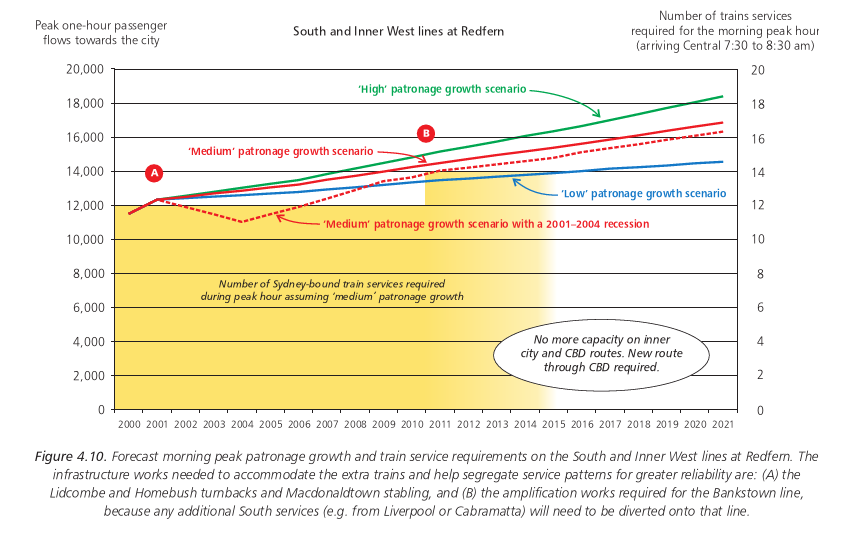

Figure 4.10 shows forecast patronage growth on the South and Inner West lines at Redfern under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1, the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario, and the timing of the infrastructure works identified as essential to permit these increases in train services, which are shown in Figures 4.7 and 4.8.

At present there is a complex and inter-weaving mix of peak services on the lines along the Main West corridor into Redfern which are used by services from the south (e.g. from Liverpool via Granville or Regents Park). The other trains using these lines include "Sector 3" services from the west, from Carlingford and from Epping.

To improve reliability as demand continues to increase, it is proposed to restore "sectorisation" and the segregation of services as much as possible in this area by:

By 2011 an additional two South trains per hour are expected to be required. Because the Main West line routes will be at full capacity by this time, these services are likely to be diverted, as "semi fast" services from Liverpool, onto the Bankstown line corridor, with associated amplification implications for that route as described above.

The essential infrastructure works on the South and Inner West corridor in the next ten years to accommodate the forecast growth are (Figures 4.7 and 4.8):

An additional turnback on the Old South line at Fairfield may also be required.

Again, after 2011 an alternative route through the CBD will be essential.

Further, several bus-rail interchanges and rail commuter car parks will need to be upgraded to cater for the increased demand, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and life safety works will be required on the City Circle, as discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

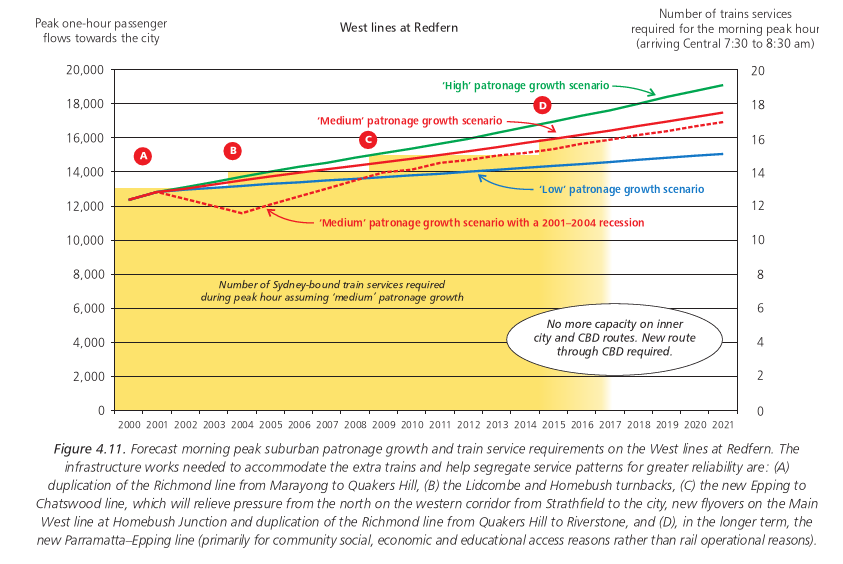

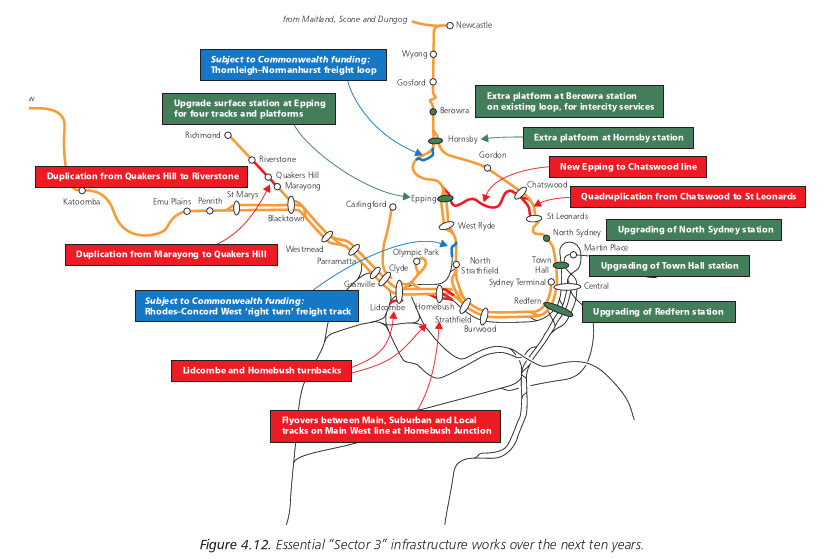

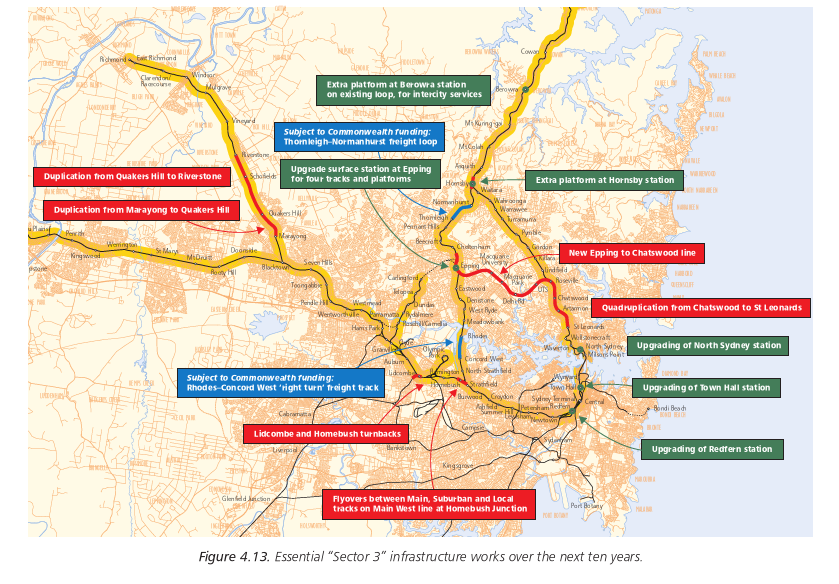

Figure 4.11 shows forecast suburban patronage growth on the "Sector 3" lines from western Sydney (Emu Plains/Penrith and Richmond) at Redfern under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1, the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario, and the timing of the infrastructure works identified as essential to permit these increases in train services, which are shown in Figures 4.12 and 4.13.

The Main West line has two tracks from Emu Plains to St Marys, four tracks from St Marys to Homebush (two of them "main" tracks and two of them "suburban" tracks) and six tracks from Strathfield to the city (two "main" tracks, two "suburban" tracks" and two "local" tracks"), with numerous "flat" junctions between these tracks and with other lines. As already indicated, there are complex interactions between West, South and North services along this corridor from Granville to the city, and the simplification of operational patterns and the restoration of "sectorisation" are essential if additional services are to be viable. Most of the Richmond line north of Marayong is a single track.

The essential infrastructure works for the West corridor in the next ten years to accommodate the forecast growth are:

This project is likely to include new flyovers between the "main",

"suburban" and "local" tracks on the Main West line at Homebush

Junction, so that services from the west can be diverted onto their

desired routes into the CBD with minimal

conflicts with other services, including services from the north

joining the Main West corridor at Strathfield, and can then travel

all the way to the city without having to swap between the tracks

again as they often have to at present.

Total cost (including an indicative $140 million for the Homebush Junction works plus other associated projects at Epping and Hornsby, described later): $1,445 million.

In the longer term, by around 2015, the construction of a new Parramatta-Epping line would provide some further capacity relief by allowing Parramatta and Carlingford line passengers bound for the North Shore to divert off the Main West corridor.

This line is, however, justifiable primarily for community social, economic and educational access reasons rather than rail operational reasons, because the combination of the proposed Lidcombe and Homebush turnbacks, the proposed grade separation flyovers at Homebush Junction and the capacity relief from Strathfield to the city provided by the Epping-Chatswood line will allow the Parramatta-Epping line to be deferred for many years. (As indicated in section 5, these projects will also permit the long-term deferral, for at least 20 years, of very expensive and disruptive track amplifications, requiring large-scale land acquisitions, on the Main West line between Granville and Strathfield.)

If the Parramatta-Epping line is constructed, it is likely that the preference will be for a terminating underground station at Parramatta rather than the earlier proposal for trains from the west to divert off the Main West line onto the new line at Westmead. This would provide much simpler, more robust and more readily "sectorised" operating patterns, and the capacity relief intended to be provided by the Westmead diversions is more readily and flexibly achieved by the means indicated above.

Further, even if the full Parramatta-Epping-Chatswood relief line

were constructed, the combined capacity of the West, North and North

Shore corridors into the city is still expected to be exhausted by

around 2015 (compared with around 2011 for other corridors into the

city), necessitating a new route through the CBD if rail is to be

able to cater for future growth in the west.

In addition, as for the other corridors, several bus-rail interchanges and rail commuter car parks will need to be upgraded to cater for the increased demand, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and life safety works will be required on the underground lines and stations in the CBD, as discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

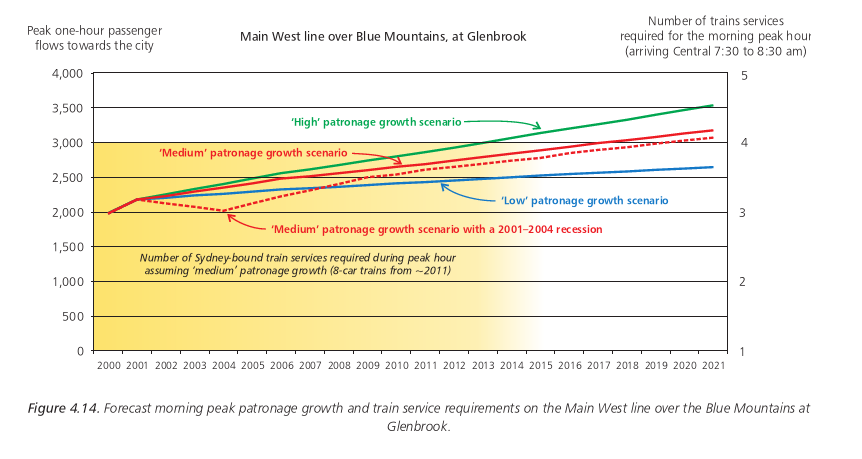

Figure 4.14 shows forecast patronage growth on the Main West line over the Blue Mountains at Glenbrook under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1.

With the boosting of some six-carriage trains to eightcarriage trains there is expected to be sufficient capacity on the Blue Mountains line to cater for growth over the next 20 years, and no capacity-enhancing infrastructure developments are proposed in this timeframe.

The key difficulties faced by these services are those associated with the highly congested West entry into the city, discussed above.

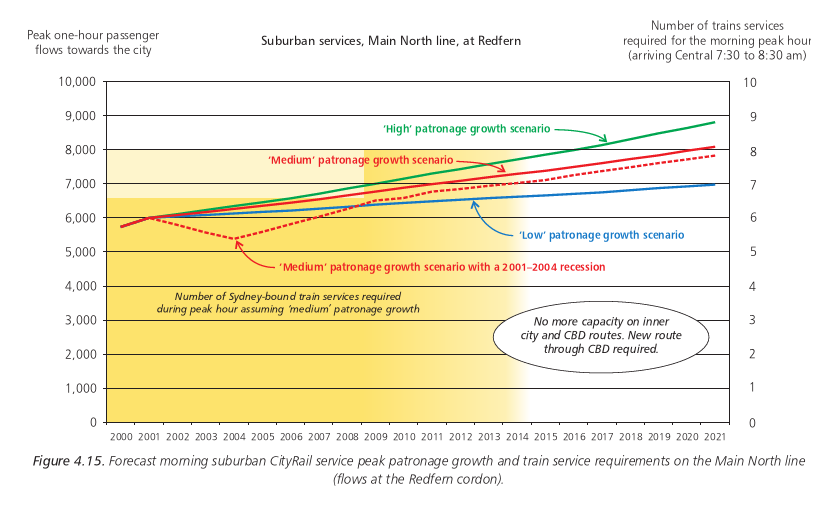

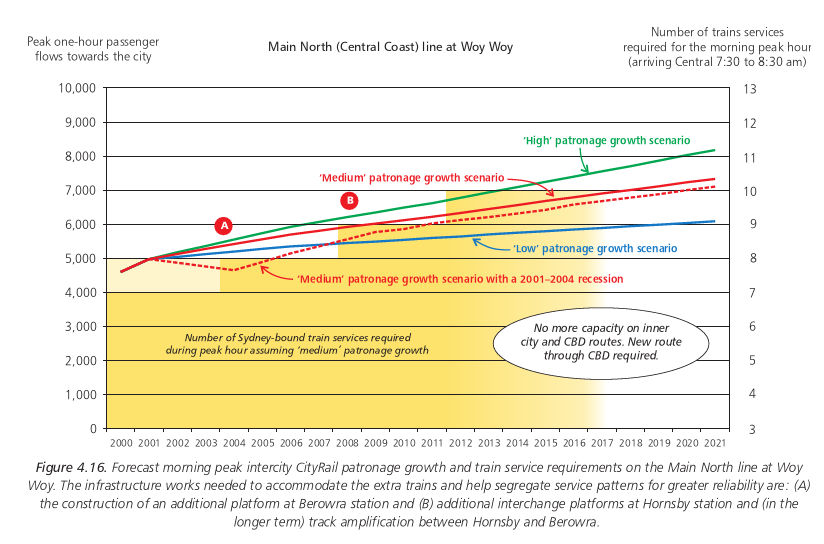

Figure 4.15 shows forecast patronage growth on suburban CityRail services on the "Sector 3" lines from the north (via the Main North line through Epping) at Redfern under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1, the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario. Figure 4.16 does likewise for intercity CityRail services on the Main North line at Woy Woy.

Most of the Main North line has two tracks, but there are some sections with three tracks -- mostly where there are passing loops or "refuges" or a dedicated freight track, such as the section between Rhodes and North Strathfield, but also including a short three-track section through Epping station -- and there are four tracks between West Ryde and Epping and on a short section between Pennant Hills and Thornleigh.

Existing Central Coast intercity services are running at capacity, but the necessary additional capacity can be provided by boosting some six-carriage trains to eight-carriage trains and by utilising a train "path" currently used for a low-patronage two-carriage service to Parramatta.

The essential infrastructure works to accommodate forecast growth on the suburban Main North corridor in the next ten years, from a passenger services perspective, are (Figures 4.12 and 4.13):

This project is also likely to include:

This project is also likely to include:

These works will need to take account of plans for longer-term amplification of the Main North line through Hornsby, including quadruplication of the line from Epping to Hornsby and triplication or quadruplication from Hornsby to Berowra, as foreshadowed in section 5.

Other enhancement works north of Hornsby considered necessary at the time Action for Transport 2010 was being prepared are now considered, on the basis of the later patronage growth analyses conducted for the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail, as being highly unlikely to be required in the medium term. This is because the proposed increase in the size of existing trains and the scope for an additional service, as discussed above, will be able to provide up to 2,500 extra seats in the medium term.

To achieve the benefits of the proposed new high-speed tunnelled passenger line from Hawkesbury River to Mt Ku-ring-gai, it will be necessary to meet the following prerequisites:

Subject to the availability of Commonwealth funding, freight services on the Main North corridor would benefit from the early construction, within five years, of:

Figure 4.17 shows forecast patronage growth on the North Shore line at Waverton under the four growth scenarios summarised in section 3.1, the timing of the extra train requirements associated with the most likely of these scenarios, the "medium growth" scenario.

With the addition of at least four peak trains per hour from the new Epping-Chatswood line the practical capacity of the two-track North Shore line will be exhausted by 2013 at the latest.

The only essential infrastructure capital project to cater for forecast growth on the North Shore corridor in the next ten years (Figures 4.12 and 4.13) are:

Again, however, after 2011 the construction of a new alternative route through the CBD, linking Eveleigh and St Leonards via the CBD and North Sydney, will be essential, so that this route into the city can accommodate additional trains from the Epping-Chatswood line, including at least four extra services per hour from the new Epping-Castle Hill-Mungerie Park line announced in Action for Transport 2010 (see section 5).

As for the other corridors, several bus-rail interchanges and rail commuter car parks will need to be upgraded to cater for the increased demand, as discussed in section 4.6, significant fire and life safety works will be required on the underground lines and stations at North Sydney and in the CBD, as discussed in section 4.7, and significant upgrading of the capacity of electrical systems will be required, as discussed in section 4.8.

In the longer term amplification of the North Shore line north of Chatswood, perhaps to Gordon, may become necessary if traffic moving onto the Epping-Chatswood line from the new Mungerie Park line reduces the number of Central Coast and Hornsby trains able to use the Main North and Epping-Chatswood route.

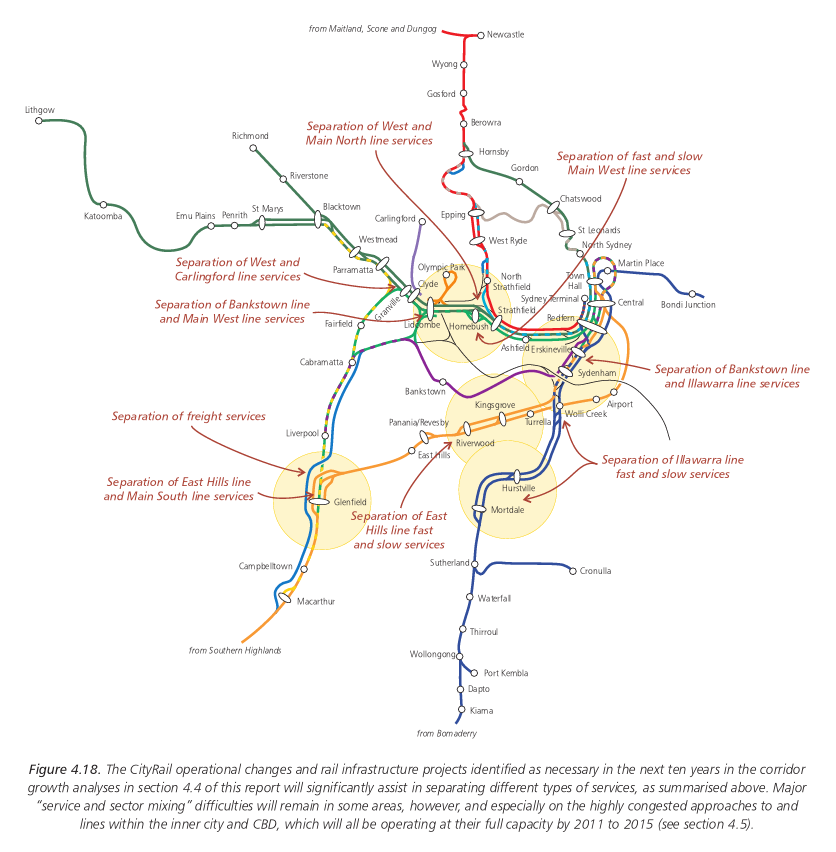

The changed CityRail service operational patterns and additional rail infrastructure identified in the corridor analyses above as necessary to enhance reliability and capacity and reduce junction and turnback conflicts will produce a significant improvement in the physical separation -- and hence the operational robustness and on-time running -- of different types of CityRail services, as summarised in Figure 4.18.

For example, the grade separations and turnbacks on the Main West line at Lidcombe and Homebush will permit all suburban CityRail services from the west to move onto the "suburban" tracks -- thereby leaving a clear path for intercity services from the north to move onto the "main" tracks at Strathfield -- without creating conflicts with trains coming from the city, Inner West trains on the "local" tracks or trains terminating at Lidcombe or Homebush. The need for trains from the west or north to change tracks again further towards the city will also be removed.

Major difficulties with the mixing of different types of services and

the non-separation of service "sectors" will remain in some areas,

however, including the "Cumberland line" from Macarthur to Blacktown.

These difficulties will be especially acute on the highly congested

approaches to, and lines within, the inner city and CBD, which will

all be operating at their full capacity by 2011 to 2015

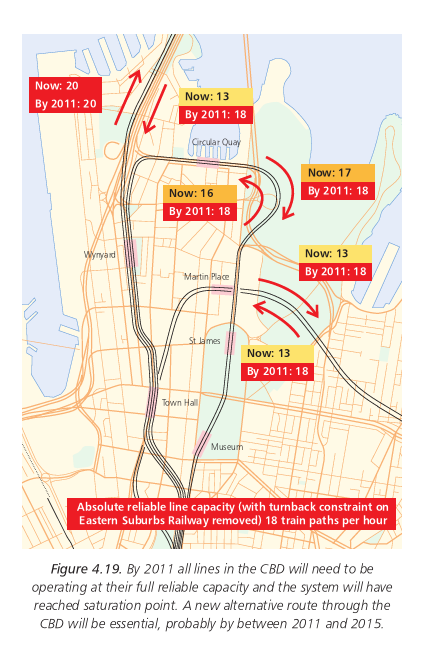

As will be evident from the discussion above, despite all the operational refinements proposed on all the corridors into the city and all the infrastructure upgrades required to accommodate demand growth in the short to medium term, the inner city lines will all be saturated within the next ten years or so (Figure 4.19), and there will be a need for a new, alternative route through the CBD, from Eveleigh to St Leonards, in the medium term, most likely by between 2011 and 2015.

In essence the situation now is analogous to that before the Eastern Suburbs Railway was built in the 1970s. By providing a new route through the inner city and CBD, the Eastern Suburbs Railway provided vital relief for the City Circle and the North Shore line through the CBD, but this capacity relief will shortly be completely used up, even with all the capacity augmentations discussed in sections 4.3 and 4.4, and another additional route through the CBD will very soon be required.

This project is regarded as being of the highest priority. Without

it, the metropolitan rail system will face strangulation and

progressive operational collapse -- and the

solutions if this occurs will all have very long lead times, of up to

ten years or more.

Preliminary investigations into the options for such a new route are now nearing completion. It is regarded as essential that the route should:

The harbour crossing options include rail tunnel options -- some routes might necessitate undesirably deep station(s) in North Sydney, but others might not -- and the resumption of the two eastern lanes of the Harbour Bridge (restoring the form in which the bridge originally operated), with bus lane and/or general road traffic requirements being met by constructing a supplementary roadway within the latticework under the existing bridge deck or (much less desirably, and from the viewpoint of the Government's public transport objectives counter-productively) another road tunnel.

The options from North Sydney to St Leonards include quadruplication of the existing North Shore line or a new and more expensive underground route with a possible new station in Crows Nest.

Options for the staging of the works and the operational implications of these options will need to be very carefully considered. For example, it might be desirable to quickly build and open an initial new CBD station accessed from the south, in order to provide some immediate capacity relief for the existing CBD lines and Town Hall station while construction of the new line northward through the CBD and across or under the harbour continues. Similarly, there could be advantages in constructing and opening the St Leonards-North Sydney section as an interim measure before the harbour crossing is established.

Once the initial investigations have more clearly identified the route and staging options and their operational implications a relatively early decision will need to be made by the Government, as a lead time of at least ten years is likely to be required before construction of even the first stage or stages could be completed.

In short, if rail patronage grows as expected, and even if it grows much more slowly than expected, there is now no time to spare.

Because of the complexity of almost all aspects of the project, it is

essential to start serious planning for this new line immediately.

| Reservation and protection of longer term rail corridors |

|---|

| There is an urgent need to commence the planning controls, land acquisitions and other actions required to protect the opportunity to build new surface and underground railway lines in the metropolitan area. |

| These actions need to commence immediately and continue throughout the next decade -- at an estimated cost of around $15-20 million per year -- but for convenience the routes involved are considered in the context of longer-term plans for the rail system, in section 5 of this report. |

| Rolling stock requirements |

|---|

| Rolling stock acquisition and replacement requirements and maintenance strategies, both within the next ten years and in the longer term, are separately discussed in section 6 of this report. |

As indicated in section 4.4, capacity-enhancing station upgrades will be required within the next ten years at Town Hall, Redfern, Sydenham, Glenfield, Sutherland, Parramatta, Homebush, Lidcombe, Burwood, Newtown, Epping, Berowra, Hornsby, Chatswood and North Sydney stations.

By far the most urgent of these projects is the upgrading of Town Hall station, which is already operating at saturation capacity during peak periods and is significantly affecting the reliability and capacity of the rail system, with station dwell times having to be as long as 90 seconds.

In other station and interchange projects over the next ten years,

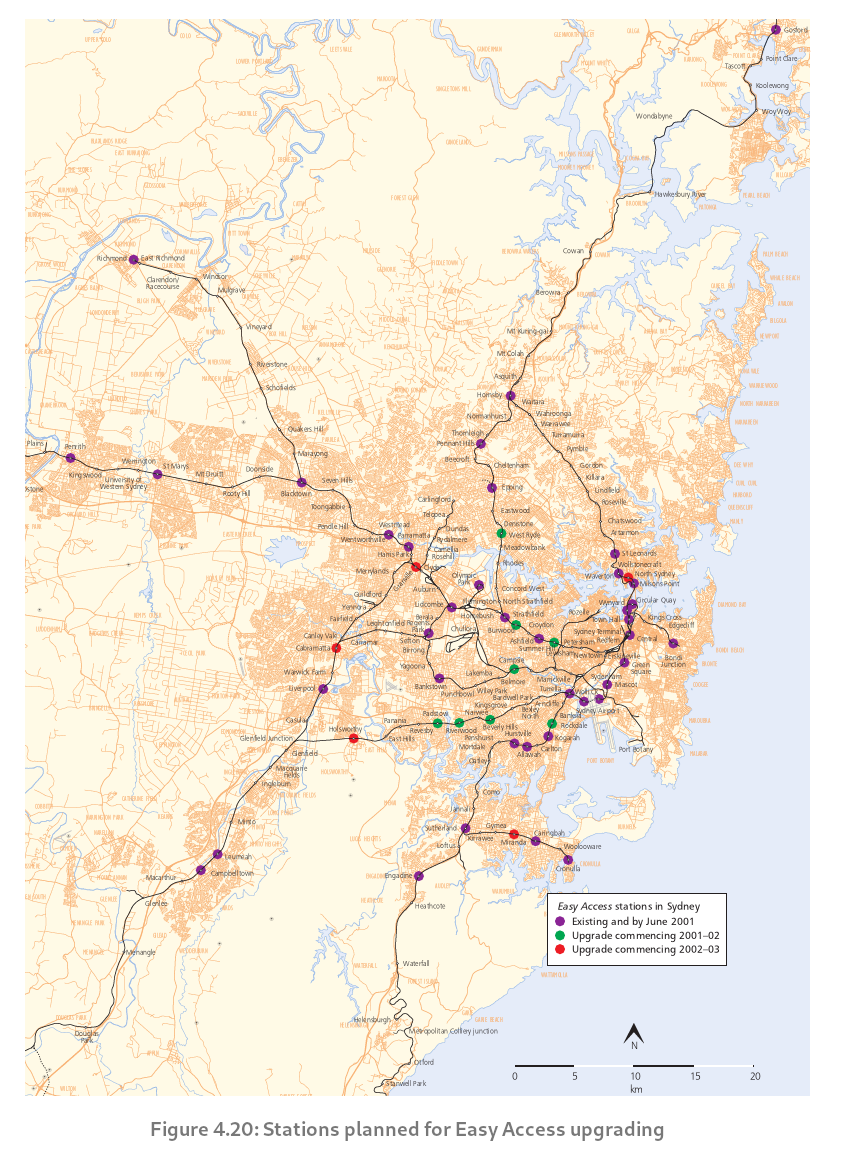

The stations planned for upgrading (Figure 4.20) are:

Further upgradings may be required, in accordance with the final Transport Disabilities Standards, even though there will be rapidly diminishing returns from these investments. The last 60 stations, each with fewer than 100 passengers per day, serve only 0.2% of CityRail's customers.

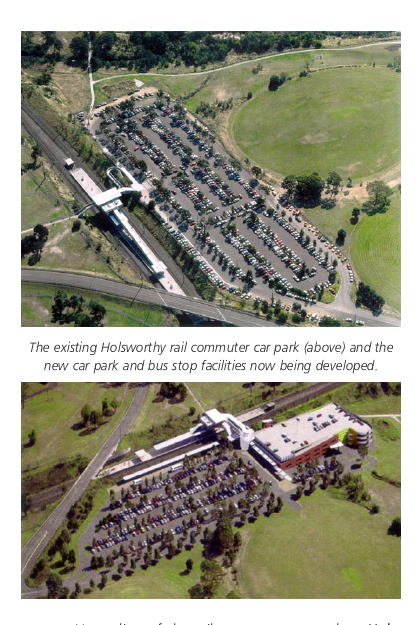

These facilities are important for CityRail's patronage growth, as approximately 23% of all journeys to work by rail also involve bus transport (the proportion is much higher at several larger suburban and intercity stations) and there has been a rapid increase in car-rail interchanging at many stations.

Priorities for these projects are assessed by the Department of Transport on the basis of Government commitments such as those in Action for Transport 2010, intermodal patronage forecasts, associated proposals by State Rail for station upgrades, analyses of regional economic costs and benefits, Government decisions and local community representations. Most of the funds required come from parking space levies in the CBD and other major centres.

Current Department of Transport plans, not yet approved by the Government, assume parking space levy revenue will total $40 million per year, not all of it for rail-related project, and therefore involve some significant delays in addressing existing problem areas. To take but one example, at Sutherland large numbers of rail commuters are already being forced to park in surrounding streets, and this is causing considerable local resentment, but rail commuter car parks in the area are not scheduled for upgrading for many years.

Further, the impacts of a number of the Department of Transport's preliminary concepts for expanded car parks on CityRail and "feeder" bus patronage and operations still need to be examined. If the locations of major car parks are not carefully planned, these facilities have the potential to actively encourage greater car travel at the expense of bus services and the use of local railway stations, while producing little if any gain in total rail patronage. This result would undermine the Government's public transport objectives, and clearly needs to be avoided.

The main rail-related interchange projects over the next ten years currently envisaged by the Department of Transport (with highly indicative costings) are:

Investigations by State Rail and Rail Infrastructure Corporation and its predecessors in the years since the disastrous Kings Cross Station fire in London in 1987 have disclosed potentially serious shortcomings in fire and life safety systems for the underground portions of the rail network (other than the new Airport line, for which the most modern control measures have been implemented).

These investigations have included risk assessment studies for the SRA in 1995 and 1996, an emergency services test exercise ("Blue Rattler") in May 1997 and a further risk assessment study for Rail Access Corporation in 1998. The risk assessments have all concluded that the current risks are above acceptable limits.

The greatest hazard is a train fire in a tunnel, and especially the smoke and fumes from such a fire, which would cause major problems not only in the tunnel but also in the stations. While the probability of such an incident is very small, the consequences could be extremely serious.

As a result of these investigations, a suite of urgent safety initiatives has been developed, with priorities being determined on the basis of achieving the greatest possible reductions in risks.

The major components of these works are:

Because of the significant cost of the measures identified in past studies as necessary -- $114 million for the tunnel smoke management systems, about $51 million for the underground stations and about $13 million for the remaining other works -- additional risk evaluations are now being carried out, to re-check the justifications for the various works in the light of a new RIC Safety Risk Standard.

If the need for the currently proposed program of works is confirmed, expected to be divided into five segments, staged over the period from June 2002 to December 2006: Wynyard and Town Hall, Museum and St James, Redfern to Martin Place, Kings Cross to Bondi Junction and North Sydney.

Electrical systems in the greater metropolitan region will need to be upgraded to cope with increased power requirements arising from:

Further, although the high-voltage (33 kV and 66 kV) system supplying power to the substations was largely rebuilt during the 1960s, the spare capacity built into the system at that time has now been used up by load growth, and the high-voltage system is showing serious signs of impending overloading.

By 2006 the total load imposed by CityRail services is expected to be about 20% higher than at present, by 2011 it is expected to be 45% higher than at present and by 2021 it is expected to be about 70% higher than at present. These increases will necessitate the upgrading of the capacity of substantial sections of the electrical supply system.

Essential and urgent electrical supply capacity improvements in the five years to 2006 are expected to cost $30 million. Detailed cost estimates have not yet been prepared for the works required in the following years, although an initial identification has been made of the components of the electrical system most likely to require upgrading as electrical demand progressively increases, and substantial additional expenditure, of several tens of millions of dollars, is likely to be required.

In the longer term, the conversion of parts of the intercity network from 1,500 V DC power to 25 kV AC power, reducing electrical rail infrastructure requirements and permitting the use of more powerful trains, is likely to be an attractive proposition.

These "Indication of Automatic Signalling Sections (IASS)" works are expected to be completed throughout the metropolitan network by the end of 2002.

Accordingly, interim technological approaches -- most of which will not be able to be used by the new metropolitan signal control system when it is later installed -- will need to be adopted to achieve rapid expansion of the Train Location System's coverage.

Stage 1 of a "Train Operations Management System (TOMS)" program to achieve this interim coverage would utilise data from the Metronet and Countrynet train radio systems, which have been subject to reliability problems and are increasingly outmoded and difficult to service, plus inputs from existing signalling and electrical control systems and the new IASS "dark territory" monitoring systems, to provide coverage from Como to Waterfall, from Epping to Rhodes and from Lapstone to Katoomba, at an estimated cost of $4 million.

Stage 2 would provide complete coverage in the area bounded by Wyong to the north, Lithgow to the west, Macarthur to the southwest and Bomaderry to the south, at a an additional cost of $8 million, by 2003.

The most immediate priorities are resignalling to reduce train headways on the Main South line between Glenfield and Campbelltown (see section 4.4), signalling modernisation on the Illawarra and Cronulla lines from Oatley to Cronulla and in the area controlled by the Sefton signal box.

The costs of these and other resignalling projects are incorporated into the major periodic maintenance costings summarised in section 4.10.

The proposed program to pilot a communications-based signalling

system, which could ultimately replace the existing conventional

signalling technologies in at least some sections of the network, has

already been discussed in section 4.3.

At present there are some 44 signal control locations in the portion of the metropolitan rail network south of Wyong, including 35 signal boxes. They control 78 different signal "interlockings" -- discrete areas of control -- using a mixture of mechanical, electrical relay and (in a few cases) computerbased technologies.

The signal control locations are based on the capabilities of the equipment being used early in the 20th century, and in most cases do not reflect the needs or capabilities of modern signal control and rail network management systems or practices.

Interactions between the various control locations are not automated and are heavily reliant on labour-intensive telephone, telegraph and fax communications.

Most of the signal boxes are more than 40 years old, and most use thoroughly obsolete technologies at least 20 years old.

Many of the systems now being relied upon for the safe operation of the rail network have already reached or are approaching the end of their effective working lives, and are becoming increasingly unsupportable. They are very maintenance-intensive, spare parts are dwindling (many parts are no longer manufactured) and modifications are both difficult and costly to implement.

Facilities for staff operating these systems are also extremely poor in many locations.

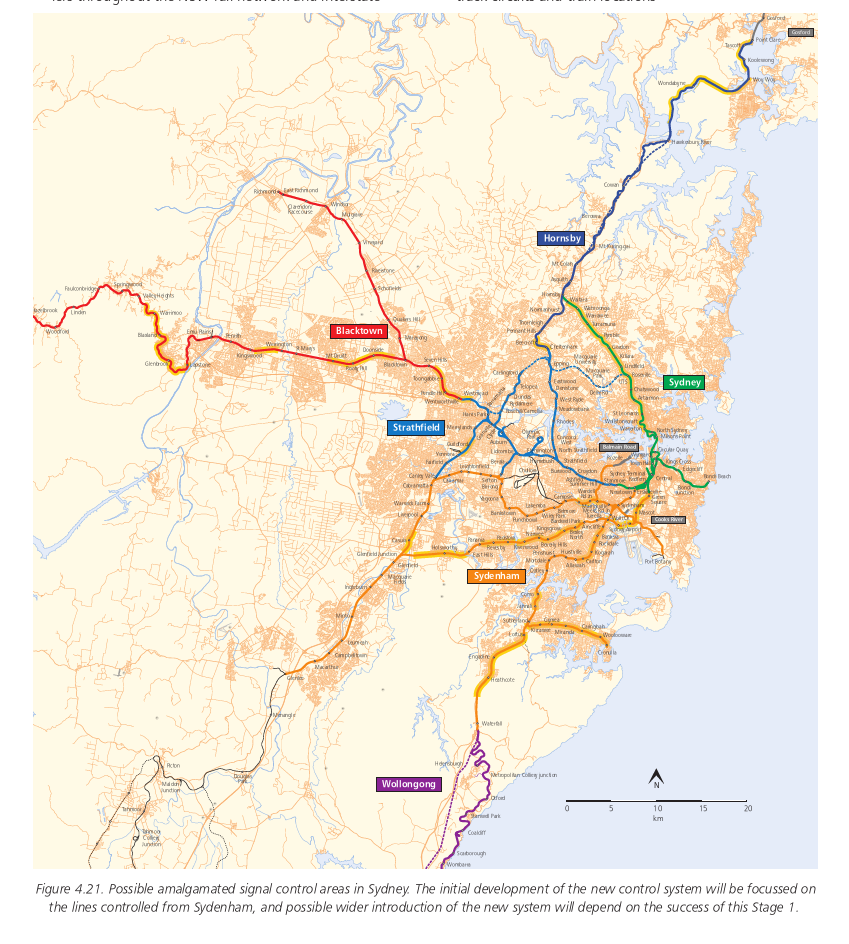

It is therefore proposed that over the next decade -- subject to the success of Stage 1 installations now commencing at the Sydenham signal control centre -- a new computerised "Metropolitan Signal Control System" should be progressively introduced throughout the metropolitan rail system, with the current scattered and outmoded signal control locations being replaced by seven modern control locations (Sydenham, Sydney, Strathfield, Blacktown, Hornsby, Broadmeadow and Wollongong) (see Figure 4.21).

This system, already introduced for the Olympic rail loop and the Airport line, will be able to control both relay-based and computer-based signalling technologies, with automatic logging of all signal system input and output data transfers, and will display the status of and data from all the metropolitan network's signalling systems, including all automatic signalling areas.

It will:

The automatic logging of information and easy generation of detailed reports will facilitate rapid examinations of incidents and equipment needing attention and assist in the development of more efficient "reliability-centred" preventative maintenance strategies, based on the actual operational performance of rail infrastructure.

The new system will necessitate modernisation of very old signal systems in a number of areas not currently able to be remotely controlled, in addition to the Oatley-Sutherland- Cronulla and Sefton projects already mentioned, including sections of the Main West line (between Auburn and Granville, at Clyde, between St Marys and Penrith and at Katoomba and Mt Victoria, and possibly later at Hartley Vale, Newnes Junction, Lithgow Yard and Lithgow), the Main South line (at Campbelltown) and the Main North line (at Gosford and a number of other locations).

An indicative estimated total cost of the project is $130 million,

including $22 million for the initial resignalling projects south of

Gosford (other than Oatley-Sutherland- Cronulla and Sefton) but

excluding any works at Gosford or north of Wyong. Stage 1, for the

control of the Sydenham, Wolli Creek, Port Botany, Wardell Road,

Campsie/Bankstown, and Hurstville areas from Sydenham, has been

costed at approximately $25 million.

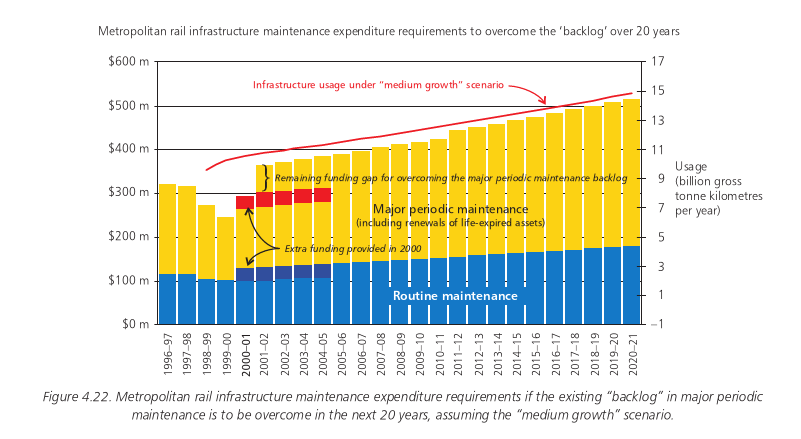

As discussed in section 2.3, one of the main factors in the degradation of rail infrastructure reliability in the greater metropolitan region in recent years has been the downgrading of many "major periodic" maintenance programs during the 1990s.

These programs included a track strengthening and concrete resleepering program, a signalling modernisation program, an overhead wiring modernisation program, a junction renewal and upgrading program and ballast cleaning, track tamping, rail grinding, timber resleepering and rerailing programs.

The downgrading of these programs has now resulted in a serious major periodic maintenance backlog, degraded asset quality and reliability, a consequential reduction in CityRail on-time running and increased day-to-day routine inspection and maintenance costs. Even with increased funding, this backlog will be difficult to overcome, as Rail Infrastructure Corporation's major plant items are old (many items were mothballed) and incapable of meeting production requirements. Even if urgent orders are placed, critical high-efficiency equipment may not be available for some time.

The Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail reports recent RIC analyses of the expenditures required for both routine and major periodic maintenance of its various classes of infrastructure assets, both:

| Table 4.1. Indicative estimates of future metropolitan rail infrastructure major periodic maintenance requirements, including prioritised works to overcome the current "backlog" over the next 20 years | |||||

| Asset type | Program | Next 10 years ( to 2011) | Following 10 years (to 2021) | ||

| % renewal | Expenditure (2001 A$) | % renewal | Expenditure (2001 A$) | ||

| Track | Resleepering (concrete replacing timber) | 60% | $201.9m | 40% | $134.7m |

| Resleepering (concrete replacing concrete) | 0% | - | 2% | $0.6m | |

| Resurfacing | 75% | $11.2m | 50% | $7.4m | |

| Rerailing | 35% | $130.2m | 35% | $130.2m | |

| Reballasting | 20% | $223.2m | 20% | $223.2m | |

| Rail grinding | 1,000% | $74.4m | 1,000% | $74.4m | |

| Ballast cleaning | 20% | $94.5m | 20% | $94.5m | |

| Turnouts renewal | 40% | $365.1m | 40% | $365.1m | |

| Turnouts upgrading | 40% | $51.6m | 40% | $51,6m | |

| Track drainage systems | 50% | $52.5m | 30% | $31.5m | |

| Junction renewals (six) | 100% | $180.0m | - | - | |

| Track slabs | 10% | $8.2m | 10% | $8.2m | |

| Miscellaneous | 100% | $46.5m | 100% | $46.5m | |

| Total | $1,439.3m | $1,167.8m | |||

| Electrical | Transmission lines | 20% | $1.7m | 20% | $1.7m |

| Substations, section huts, HV switching | 20% | $73.4m | 20% | $73.4m | |

| Overhead wiring and OHW structures | 10% | $122.4m | 20% | $244.8m | |

| Miscellaneous | 100% | $18.6m | 100% | $18.6m | |

| Total | $462.7m | $483.5m | |||

| Signalling | Lineside signalling | 35% | $70.6m | 35% | $70.6m |

| Trunk cabling systems | 25% | $300.5m | 25% | $300.5m | |

| Interlockings | 25% | $12.6m | 25% | $12.6m | |

| Signal control points | 35% | $2.8m | 35% | $2.8m | |

| Remote control systems | 50% | $2.3m | 50% | $2.3m | |

| Signals | 50% | $16.1m | 50% | $16.1m | |

| Worked points/point ends | 20% | $11.1m | 40% | $22.2m | |

| Train stops | 20% | $9.6m | 40% | $19.3m | |

| Miscellaneous | 100% | $37.sm | 100% | $37.2m | |

| Total | $462.7m | $483.5m | |||

| Communications | General systems | 50% | $75.0m | 50% | $75.0m |

| Train radio | 25% | $20.0m | 25% | $20.0m | |

| Total | $95.0m | $95.0m | |||

| Bridges | Overhead parapets | 20% | $4.6m | 20% | $4.6m |

| Overbridges | 5% | $35.8m | 10% | $71.5m | |

| Underbridges/flyovers/viaducts/transoms | 10% | $21.4m | 10% | $21.4m | |

| Culverts/subways | 10% | $3.7m | 10% | $3.7m | |

| Footbridges/service bridges | 10% | $5.2m | 10% | $5.2m | |

| Total | $70.6m | $106.3m | |||

| Land and buildings | Access roads | 50% | $2.3m | 50% | $2.3m |

| Fences | 10% | $5.5m | 10% | $5.5m | |

| Cuttings and embankments | 10% | $0.8m | 15% | $1.28m | |

| Existing noise barriers | 0% | - | 5% | $0.4m | |

| Removal of disused structures | 20% | $2.5m | 20% | $4.8m | |

| Level crossings | 75% | $14.3m | 25% | $4.8m | |

| Weighbridges | 33% | $1.0m | 67% | $2.0m | |

| Retaining walls | 10% | $13.0m | 167% | $217.1m | |

| Total | $39.3m | $235.7m | |||

| Tunnels | Tunnels and rock shelters renewal | 20% | $24.0m | 10% | $12.0m |

| Total | $2,347m | $2,439m | |||

The "steady state" major periodic maintenance and routine maintenance expenditure requirements identified by RIC are broadly in line with 2001 funding levels, which were boosted by the Government late last year (in the case of metropolitan rail infrastructure maintenance, by $40 million per year, and in the case of the renewal of life-expired metropolitan rail infrastructure assets, by $20 million in 2000-01 and by $30 million per year thereafter). However, the total major periodic maintenance expenditures needed in the years ahead, so the current backlog can also be addressed, even over a very extended period of some 20 years, are: