| Action for Public Transport (N.S.W.) Inc. |

| P O Box K606 |

| Haymarket NSW 1240 |

| 30 March 2020 |

Action for Public Transport (NSW) ("APT NSW") is a transport advocacy group active in Sydney since 1974. We promote the interests of beneficiaries of public transport; both passengers, and the wider community.

Key points

Given the lack of success of previous motorways to reduce congestion and improve travel times, it is not sensible to expect a different result in the case of the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link.

In any event, the proposal is at odds with the State's integrated transport and land use plans and with its intention to transition to net zero emissions by 2050.

Many public transport improvements in both urban and regional areas are canvassed in Future Transport 2056, and in other strategic documents, but cannot progress unless funding is made available. They should have priority over a motorway to the Northern Beaches of Sydney.

Starting point

A 2014 NSW Audit Office report1 notes (p.15) that the Westconnex project began with the NSW Government asking Infrastructure NSW (established mid-2011) to provide advice on "Sydney's next motorway priority" as part of its work in developing the State Infrastructure Strategy (SIS). Exactly when and how this request was made is not indicated in the report. Nor is it clear why the request was made, presuming as it does the need for a motorway at all.

The reason may be the one alluded to in a March 2012 report by the National Infrastructure Co-Coordinator2, which stated (p.29) "There have been suggestions that Transurban may present an unsolicited proposal to the NSW Government to develop several motorway links".

The opaque "unsolicited proposals" process that delivered the Westconnex proposal then produced the "Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link".

The proposal has now leapt straight from a "scoping" paper in 2017 to an EIS in 2019. At no point has the proposal been the subject of a proper process of strategic justification.

Although the EIS deals with the Western Harbour Tunnel and Warringah Freeway Upgrade, there is frequent reference to Beaches Link and it is seen as "an integrated program of works known as the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link program" (Chapter 3 p.3-9).

We note tolling facilities are to be built in, indicating sale to a toll operator. It is easy to see why a tollway connecting a high-income area to the established CBD and the airport would be an attractive proposition for a tollway operator. How and why the proposition would get this far without proper, open assessment is a mystery worthy of investigation.

Strategic Context

Integrated transport and land use planning

The EIS presents the proposal as consistent with the strategic transport plans simply because it is "referenced". APTNSW regards this as a misrepresentation. The list of committed road initiatives on p.77 of the Greater Sydney Services and Infrastructure Plan includes the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link (subject to Final Business Case) (emphasis added). No "business case" has been produced.

The highest priority identified in integrated transport and land use planning is clearly (and correctly) improving public transport. The Greater Sydney Services and Infrastructure proposes "a coordinated approach to land use, transport and infrastructure" (p.46) and states:

As part of this integrated approach, we will deliver services and infrastructure that enable 30-minute access by public transport (emphasis added):The Strategy proposes to achieve this by:

- For people in each of the three cities to jobs and significant services in their nearest Metropolitan City Centre or Cluster - the Harbour CBD, Greater Parramatta or, in the Western Parkland City, WSA-Badgerys Creek Aerotropolis, Greater Penrith, Liverpool and Campbelltown-Macarthur. This will help drive the productivity of our city by effectively connecting people and jobs.

- For residents in each of the five districts to their nearest Strategic Centre. This is important for the liveability of Greater Sydney, enabling people to conveniently access local jobs, goods and services

... investment in mass transit, improving service frequencies, better prioritising public transport around centres (see Figure 22) and improving walking and cycling connections to public transport.The government is planning and delivering public transport but most are uncommitted and unfunded; motorways are referenced through clenched teeth and "subject to a business case" which has never been published.

The EIS has to hark back to the 1930s for strategic justification, noting that plans were developed then for an additional Harbour Crossing to the Northern Beaches.

Since then, as the timeline on p. 4-4 and 4-5 notes, three additional crossings have been completed: Gladesville Bridge (1964); Sydney Harbour Tunnel (1992) and the tunnel associated with the railway line under construction between Chatswood and Bankstown. When that line is in operation it will offer a good alternative means for residents of Sydney's northern suburbs to access Sydney Airport.

There is no compelling strategic case for this proposed harbour crossing in 2020. As noted later in this submission, there are many more worthwhile projects that should be delivered first.

Climate change

An aspirational target in the State's Climate Change Policy Framework, zero net emissions by 2050, is intended to set NSW up as a leading and competitive low-carbon economy.

The EIS skates over the increase in VKT (vehicle kilometres travelled) clearly predicted in the climate change and green house gas calculations set out in the accompanying report. The "justification" for proceeding regardless rests entirely on the proposition (Jacobs p.40) that "greater volume of traffic which is able to flow more freely, but at an improved fuel efficiency".

This is a spurious proposition because the "free flow" of traffic it assumes will dissipate quickly as induced traffic counteracts the short-lived impact of increasing road space.

The "Do nothing" option presumably means doing nothing about public transport either (p.40). There is no reason that should be the case.

Emissions from transport are second only to energy production. Motorways in highly developed cities are part of the problem and form no part of the solution.

Expected outcome

The proposal rests on the discredited notion that increasing road space reduces congestion and travel times. This is a conventional "predict and provide" approach, and it has been known for many years that it does not work. Continual increases in road space induce continual increases in the number and length of car trips. Any improvement quickly dissipates, as empirical evidence has established time and time again.

Circular reasoning and self-fulfilling prophecies

The "predict and provide" approach is an exercise in circular reasoning and self-fulfilling prophecy.

It is based on projected population growth, from which growth in travel is assumed. Past patterns of mode share, adjusted for committed transport projects, (few of which are public transport projects) are then projected forward as "forecasts". This leads inexorably to the proposition that more road space should be constructed - to reduce congestion and improve travel times. We ought to know by now that this is a circular and futile exercise.

Induced traffic

All the road building undertaken in cities at enormous expense for more years than we care to count has failed to "solve" the problem of traffic congestion. However frenzied the expenditure, continuously adding road space fails to reduce congestion and travel times.

The problem, as has been empirically established over many years3, is a persistent failure to acknowledge the reality of induced traffic. Traffic is not like water; it is a fundamental mistake to apply hydraulic principles to transport planning.

The act of providing additional road space increases the demand it was aiming to accommodate, that is, it increases vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT). The Climate change and greenhouse gas calculations (Jacobs, 2020) forecast increased VKT.

It can be stated with a high degree of confidence that the Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link will induce more traffic to occupy the extra road space created. The Westconnex New M5 Project Overview contains empirical evidence that this is what should be expected. It notes (p.9) that the "old" M5 was congested within just six months of its opening in 2001, and now experiences the slowest typical travel speeds of any of Sydney's main motorways4.

The EIS for the M4 East unconvincingly proposed to "mitigate" the problem by adding more "Westconnex" road projects to move the bottlenecks along, one at a time5. In this case, the bottleneck is expected to move to Rozelle, where a deluge of vehicles from a "Western Harbour Tunnel/Beaches Link" would overwhelm the road system in the vicinity of Victoria Rd Rozelle and the Anzac Bridge. This induced traffic has already sparked an application (SSI7485) to amend the M4-M5 approval to construct an additional above-ground road at the expense of opportunities for active transport.

Traffic modelling predicts that the proposed Western Harbour Tunnel project would worsen the performance of intersections on the roads approaching the Anzac Bridge. This is apparent from Table 4-1, in which complying with the Minister's approval is described as "Option 1":

... the EIS design would not provide sufficient capacity for additional traffic generation should other proposed projects, including the proposed Western Harbour Tunnel and Warringah Freeway Upgrade project ('Western Harbour Tunnel project'), receive planning approval. As a result, additional works would be required at the intersection in the future resulting in increased construction works over a longer timeframe around The Crescent/City West Link intersection.Exactly the same thing should be anticipated at the other end - Northern Beaches roads overwhelmed by traffic from Westconnex.

Approval of the modification would place the Minister for Planning and the Minister for Transport in a very difficult position. If the Crescent overpass is built, the Minister for Planning will be under enormous pressure to approve the Western Harbour Tunnel/Beaches Link project and the Minister for Transport will be put under pressure to fund it, They will face an argument that the money already spent in an (ultimately futile) attempt to accommodate traffic generated by the Western Harbour Tunnel/Beaches Link project would be wasted if the project is dropped.

This is a classic "sunk cost fallacy"6, an error in reasoning also captured in the saying "throwing good money after bad". All money spent on urban motorway projects is wasted if they consistently fail to achieve their stated aim (reducing congestion). Empirical evidence consistently shows that this is the case.

The argument is however superficially plausible, and often succeeds. Decision makers can find themselves "locked in" to a particular decision irrespective of the results of any proper assessment process. Whether this is an intended outcome in this case we cannot say.

Failure to consider alternatives

The EIS purports to consider alternatives, but does not do so in any serious way. It states: "Without intervention, the predicted growth in traffic demand over time will result in further increases in journey time delays and deterioration of reliability over time" (3-4). Leaving aside the inadequacy of the “predict and provide” mentality evident in this statement, the EIS gives little serious thought to what is the most effective and least damaging intervention to address this anticipated problem.

The alternative of improving the public transport system is peremptorily dismissed in the EIS. Instead, it skips straight to "augmenting capacity" (3-6).

Moving people, not vehicles

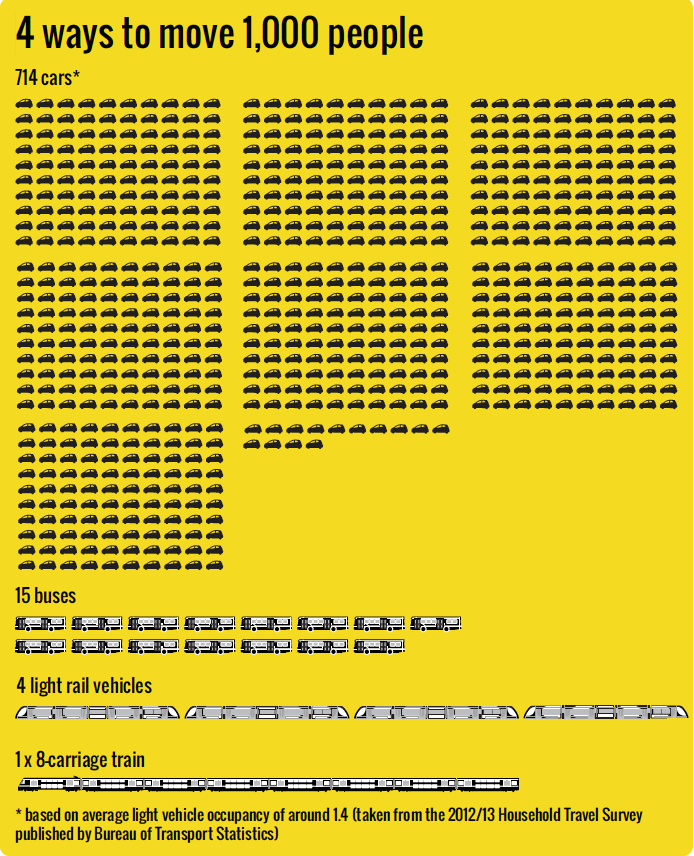

The EIS considers a proposed busway from Chatswood to Dee Why, but concludes: "improved bus services alone would not be sufficient to provide the level of additional cross-harbour capacity that is required" (4-11). Assuming we are talking about the movement of people, not vehicles, this is not the end of the matter.

The new metro railway at Chatswood connects to the northwest and is being extended south to the Sydney CBD. The capacity of a metro system greatly exceeds that of a bus system. Additional capacity and lasting benefit could be achieved by extending the metro eastwards to Dee Why, to create the long-overdue Warringah railway.

Grids and webs

The EIS is needlessly downcast about the capacities of a well-designed public transport system. It suggests that the Sydney Metro City and Southwest project will deliver much needed cross-harbour capacity but that "it is only one part of an integrated transport network that is required to serve the needs of a very diverse range of origins, destinations and journey purposes".

It goes on to suggest that "The array of journey patterns and trip purposes within Sydney, and the dispersed nature of origin and destination points for an individual journey mean that roads remain a critical element in the integrated transport network, servicing buses, freight, commercial and many other individual journey needs".

No-one seriously doubts that roads serve an important transport task, but that is not an argument for this particular proposal. Nor is it the case that public transport systems cannot serve a wide variety of dispersed trips. The secret to catering for diverse trip patterns is to increase the coverage of the public transport network, design it as a web of interconnecting routes, and run services at high frequencies7. This maximises access from any point to any other point on the web (a modified grid), and creates "network effects" (higher patronage across the whole network). This is the underlying system design principle for the very popular Metro Bus system. It is also how exemplary systems such as those found in Paris and Tokyo work.

The new cross-harbour metro

According to the EIS, "Strategic transport modelling completed by Transport for NSW indicates that there will still be need for additional road transport capacity at the crossing of Sydney Harbour to cater for future demands post Sydney Metro City and Southwest". Perhaps. It is also possible that the benefits of the cross-harbour metro system have been underestimated, and that the need for additional road capacity can be delayed.

Media reporting on 25 June 20198 noted:

"The new Sydney Metro Northwest has helped reduce traffic by more than one per cent in its first month, which NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian says has "exceeded expectations".In any event APTNSW questions how this forecast need for additional road transport capacity at the crossing of Sydney Harbour came to be ranked ahead of other pressing transport needs."Since opening one month ago there has been an average of 65,000 journeys on weekdays, taking people off motorways, buses and the existing rail network," Ms Berejiklian said.

"Over the past month 20,000 fewer cars used the M2 compared to the same time last year and up to a 20 per cent fall in usage at key stations on the T1 Western Line."

Freight and delivery vehicles

The EIS places considerable emphasis on commercial deliveries and freight movement.

The project offers no long-term relief for commercial users, because the growth in traffic induced by road space increases will continue to crowd them out. If the history of the old M5 is any guide - and it is - after a period of relief, they will find themselves stuck in traffic again, and most of that traffic will consist of passenger vehicles.

Sabotaging public transport

The climate change and greenhouse gas calculations that form part of the EIS (Jacobs, 2020) forecast increased VKT; the document suggests at p.40 that mode shift (presumably away from public transport) is part of the reason. This is worrying, and it is well founded.

Relevant ATAP Guidelines (T1 Travel Demand Modelling) contain the observation that a modal shift from public transport can account for up to half of the estimated induced traffic on a road corridor (2016, p.29). A practical example can be found in the case of the Westconnex EIS, which predicts that 45,000 journeys will switch from public transport to road trips on WestConnex on an average weekday by 2031 (Searle and Legacy, 2017, citing RMS)9

The B-line has demonstrably improved public transport services on the Northern Beaches. The effect of the Western Harbour Tunnel/Beaches Link would be to rob it of patronage and impede its effectiveness by encouraging more vehicles onto the Peninsula.

Warped priorities

The Future Transport 2056 Strategy acknowledges (p.27) the "service deficit in Regional NSW and in some areas in Greater Sydney". It notes (at p.35):

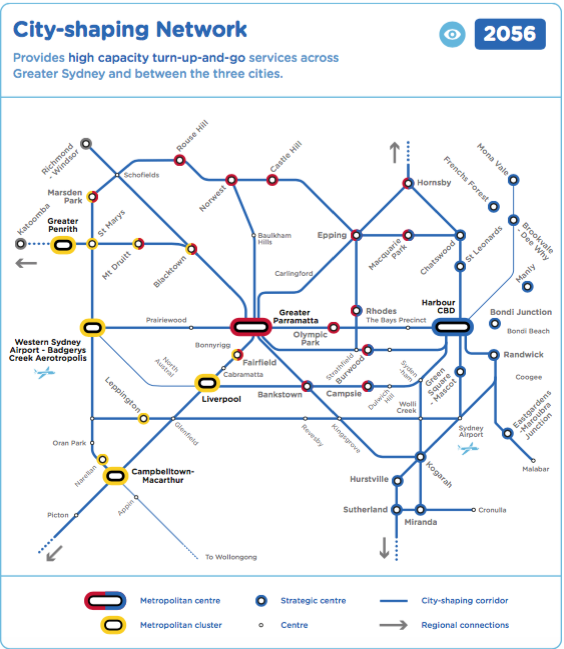

Customers tell us the main barrier to using public transport is the availability of frequent and reliable services to take customers where and when they need to go. This is especially the case in regional communities and in outer metropolitan areas, where public transport services are more limited.APTNSW appreciates that after more than 50 years of neglect, there has been significant investment in public transport services in recent years. More improvements are on the drawing board. Future Transport 2056 and its companion documents (Greater Sydney Services and Infrastructure Plan, Regional NSW Services and Infrastructure Plan, Greater Newcastle Future Transport Plan) contain many worthwhile proposals10 (See Attachment 1). The proposed network for Sydney (shown as Figure 56 in the Strategy) is reproduced as Attachment 2.

There are many critical public transport improvements that have not secured funding and are not on course for delivery. The problem is of course that choices have to be made, because funds are not unlimited. Westconnex is soaking up funds, but it has yet to demonstrate that it can deliver any lasting public benefit. The Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link can only worsen matters. It would do nothing to support the State's integrated transport and land use plan; it cuts across it.

APTNSW submits that the public transport improvements set out in Future Transport 2056 should be delivered before further thought is given to constructing a motorway to the northern beaches of Sydney. Higher priority should also be given to projects that would untangle freight rail from passenger rail (such as the partially completed Maldon-Dombarton line), to the benefit of both systems.

Faster rail

There are a number of promising proposals for faster rail to regional centres that should have higher priority than this proposal. Victoria's Regional Rail Program is providing a useful demonstration of what can be achieved. It is pleasing to see that Federal funding ($2 billion) is now in place to help deliver faster rail (averaging 160km/h) between Melbourne and Geelong.In NSW, projects offering comparable benefits include upgrading the Newcastle line and the South Coast line. The present 60km/h average speed achieved on the South Coast line is ludicrous11; much higher speeds could be achieved by constructing a tunnel between Waterfall and Thirroul (a distance of approximately 22km).

We are aware that the Federal Government is contributing funds for a business cases for faster rail between Sydney to Newcastle, and has announced it will also support business cases for faster rail corridors between Sydney and Wollongong, and Sydney and Parkes (via Bathurst and Orange).

Conclusion

The EIS does not provide a reasonable basis on which to approve the application. It rests on a series of fundamental misconceptions about transport, land use and cities. It fails to consider alternatives. Its reasoning runs counter to the Government's integrated transport and land use strategy and its climate change strategy.

The project will not reduce congestion and is likely to do quite the opposite. Stubborn attachment to an approach that empirically does not work can only lead to a monumental waste of public money.

APTNSW suspects that many Government members know that the "Western Harbour Tunnel - Beaches Link" will not ease Sydney's road congestion. Transport planners certainly do.

Public transport is the real congestion buster. The completion of the North-West Rail Link has achieved reductions in congestion levels. The most effective approach is better public transport coupled with demand management strategies.

The application to which the EIS relates should consequently be refused. The funding for the project should be reallocated to more worthwhile projects such as filling in missing links in urban public transport systems, disentangling the passenger rail network from the rail freight network, and providing faster rail links to regional centres.

Public transport initiatives for investigation (0-10 years)

Initiatives for investigation and possible delivery in 10-20 years are listed on p.61 and p.68 of the Greater Sydney Services and Infrastructure Plan: